My approach to the Data Warehouse and how company like Shopify should think about them.

What is the Data Warehouse?

The Data Warehouse (“DW”) is a data product that consolidates key data assets to help you understand your business and product. It forms the basis for all analyses, dashboards, and data products, providing a consistent narrative.

Data assets in the Data Warehouse come with data contracts that clearly define SLOs, ownership, and appropriate use. These assets adhere to Shopify’s data modeling standards, making them easy to work with. Data Engineers aim to deliver impactful, long-lasting, reusable, official data assets to the DW.

However, not everything belongs in the Data Warehouse.

- The Data Warehouse is not a collection of all data tables ever created at Shopify.

- The Data Warehouse does not contain all the modeled data.

- The Data Warehouse does not include all data reviewed or used by a specific tool.

The Main Story

A well-executed Data Warehouse narrates the stories of our businesses and products. It compiles all crucial information, enabling us to make informed decisions and build superior data products.

To do this, you must consider the story that is relevant to your team or area. For instance, if I work in the Shopify Payments team, my colleagues and I have a deep understanding of the data from that area. We should consider what information other teams might find useful. What are the elements that we want to present in a format that others can easily consume?

This is what you aim to reveal in the Data Warehouse. You should view these tables as a product you are creating for others to use. At this stage, you should not be thinking about a specific dashboard or question you want to answer. Your table should serve as a foundation for others to build upon.

Engineers excel at this, they have APIs. APIs provide a clear interface where you offer a specific service for others to use. It comes with a specific guarantee (SLA/SLO, etc).

What I create as a Shopify Payments data modeler is this API for others to understand my world of Shopify Payments. Our data itself is a product, and I can make an impact with it when I model it effectively for others to use and build things with.

What are the assets of the Data Warehouse?

Like APIs, the ability to query it, is only a part of the equation. Everything surrounding the actual API is even more important:

- Data tables (what people actually use)

- The code that generates the table (DBT, Spark, etc.)

- Documentation (often overlooked, but crucial. If people can’t find your data or understand it, it’s useless. This includes usage instructions, data representation, caveats, etc.)

- Metadata

- Service level agreement/objectives (SLA/SLOs)

- Maintenance

Good APIs (like Stripe’s) are known for their simplicity and cohesion. When you query Stripe’s API, you get a consistent experience across products, and standardized documentation that makes understanding multiple features easy.

Organizing the data team’s work around the org chart is a major risk when building a Data Warehouse. It might seem easy to organize data into buckets that match your org chart, but what happens when the org chart changes? What if a data product needs to cross org chart lines, and different buckets have different standards? This is why we prioritize company-wide standardization over individual team goals, and we do not organize the Data Warehouse by org chart. Instead, we organize into data domains, which exist regardless of the org chart’s state.

It’s not only about the inside

In the context of the Data Warehouse, no single table is more important than the warehouse itself. It’s like Lego bricks.

One of Lego’s strengths, and the reason it has outperformed its competition, is the quality and ease of stacking bricks. They fit together well, but are also easy to take apart. Any Lego brick can be used instantly, and you never doubt that it will connect with any other Lego bricks.

This is because all Lego bricks must fit together. They all have the same connection format, which has been consistent for all blocks ever made. The quality of that connection is also guaranteed. Lego bricks always fit together.

There might be many ways a specific block could have been optimized if it were built slightly differently, but Lego chose to optimize for the overall experience rather than each individual block. This makes them easy to work with. Lego prioritized global optimization over local optimization. This global optimization, combined with high quality standards, has allowed Lego to dominate their industry.

Designing a Data Warehouse is similar. When you start designing a table, you need to optimize for the overall good of the entire warehouse, rather than focusing on the micro-optimization of one specific dataset.

no single table is more

important than the warehouse itself.

Standardization of the Data Warehouse is one of its key requirements. Without this, we won’t have a cohesive Data Warehouse, but rather a collection of tables that barely interact with each other, much like Lego blocks that don’t connect.

The Data Warehouse Treaty

Roles

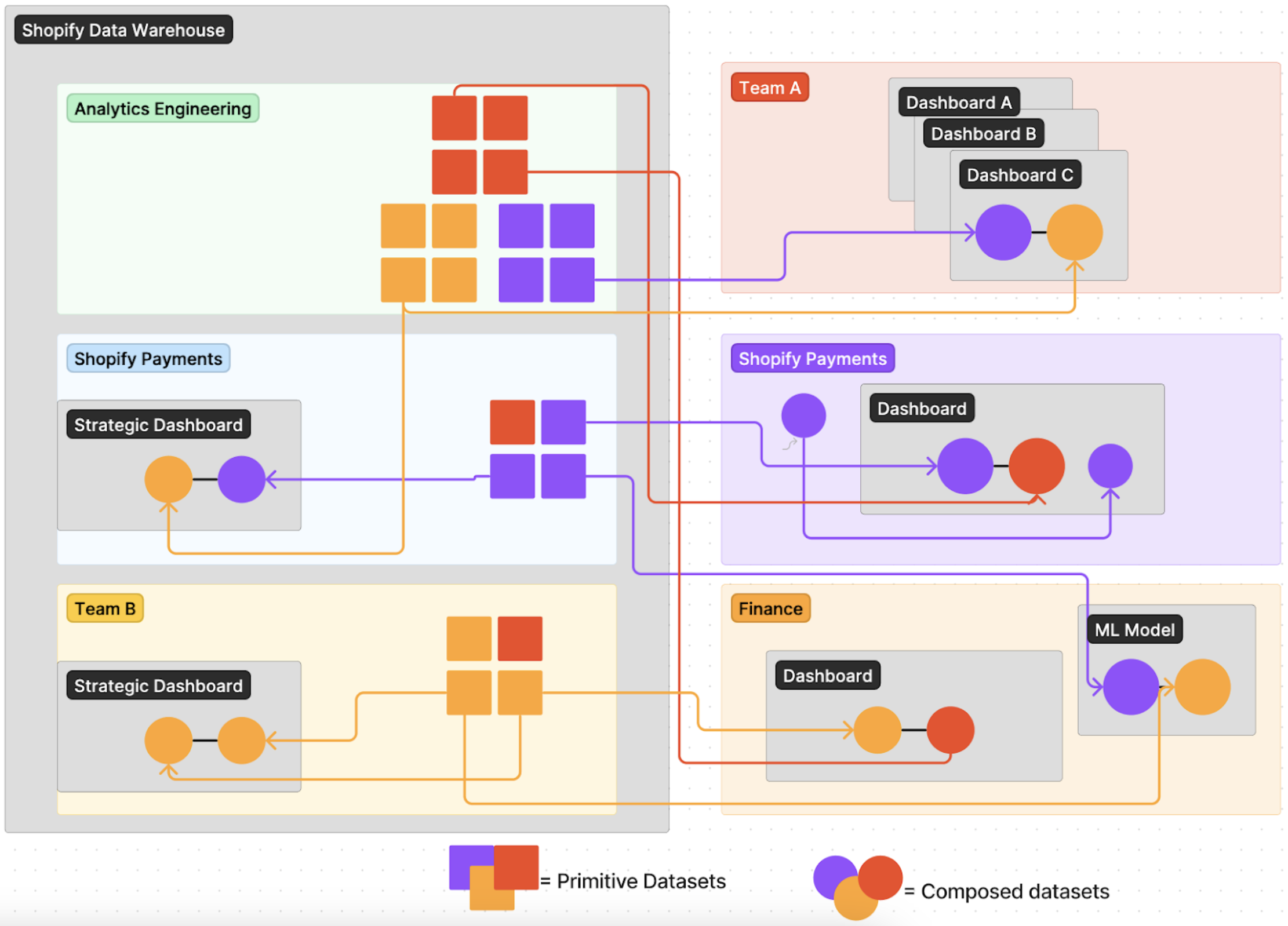

The Data Warehouse contains primitives, which you publish for others to use. This is typically where ownership between teams diverges.

Product data team

The product data team’s role is to produce the Primitives Datasets (also called Intermediate Datasets) that anyone can use to understand what’s happening in that domain. They are also responsible for documenting and maintaining these datasets, ensuring they are accurate and represent reality without unnecessary team-specific interpretation or filtering. However, it’s not this team’s responsibility to create all potential marts/dashboards/analyses that pertain to the domain. Some critical dashboards may be part of the Data Warehouse, but not all. Dashboards with a smaller scope or those not expected to last for a long time, for example, will not be included in the Data Warehouse.

Consumer data team

As a consumer, I can’t expect the owners of these tables to build everything I need. I likely have my own stakeholders who want to measure KPIs across multiple domains. It’s my role to assemble the story I need from the available primitives produced by all data teams, including my own.

For instance, if I work in the Finance team, I would like to calculate the profit and loss across Shopify. It’s my role to build my calculations using available data from all revenue-generating products, including Shopify Payments.

The role of the Shopify Payments team in this treaty is to ensure all necessary primitives exist, so the Finance team can calculate the KPIs they’re interested in. Since Shopify Payments is already treating their data as a product and shipping it to the Data Warehouse for broad, use-case independent consumption, it’s expected that I can use their data even for my Finance use case.

If Shopify Payments hasn’t yet exposed the needed data in the Data Warehouse (i.e., there are missing primitives in the dataset needed for Finance to produce what’s expected), it’s important to communicate between teams to explain requirements and the rationale for the needs.

Note that each team usually plays two roles: one as a data producer that needs to build Primitives for the rest of the company, and another as a consumer data team doing analysis, dashboards, and more. Ideally, they consume from the same datasets they offer in their slice of the data warehouse.

Conclusion

The Data Warehouse is not just a collection of tables; it’s a carefully crafted series of cohesive tables that tell the stories of Shopify, its products, and its merchants. It’s built for other internal teams or merchants to consume.

Building a world-class Data Warehouse requires treating it as a top-tier product, with high data and engineering standards.

A well-crafted Data Warehouse is greater than the sum of its parts, much like a LEGO masterpiece is far greater than the sum of the individual LEGO blocks that compose it.

Special thanks

Special thank you to some of my colleagues that helped me edit this post.