A message for all the Decision Makers (DM) using data to make decisions.

Dear Decision Maker, this is why you don’t just want quick numbers…

I am dedicating this post to all my Decision Maker friends. I wanted to share with you, why you see your data counterpart so uncomfortable when they have to produce data with low confidence aka, “just a quick number please, no need to be precise”.

Over the past years, I have seen this trend where a DM, short for Decision Maker (or any stakeholder: UX, Fiance, Legal, Product, Eng, Marketing, Partnership, etc. etc.) will come to a data team and ask for a few numbers. After a quick chat, the data scientist realizes X number of hours/days will be required to properly calculate the number in question. Right after the DM will say.. Ooo no I just need quick numbers, does not need to be precise just an estimate is good enough. 80% confidence is good enough.

Frequently, even if the data scientist disagrees with this, they do not have the political capital to push back against the DM and agree to do it. But this is wrong, it causes more damage, especially for the DM that is about to make a wrong decision.

This following article is not 100% statistically accurate, but given the target audience are DMs, I want to make it more understandable than accurate.

Here’s a different way to think about confidence

I have realized that there is a lot of misunderstanding of what a 90% confidence (or 80 or 95 or whatever) means. Example : How many customers have X enabled? If the real answer is 30%, and they expect a rough answer + or - 10%, they expect that you will give them something between 27% and 33%. If that was true, I would actually agree with them, because to make most business decisions 27%, 30% or 33% all tell the same story. If that was the case, I there would be no point to this article.

But what a (+-90% confidence) rough number really means is, there are 9 chances out of 10 that I tell you more or less 30% and 1 chance out of 10 that I tell you 86% (or some other completely random value). Something extremely wrong that will lead you to make the wrong business call.

To make the example even more visual:

Let’s take this picture. There are roughly 15 Sheep, 14 White and 1 Black.

Those Sheep are white. Like 14 out 15, or 93% are white. That being said, statistically, if you pick 1 random sheep you still have 7% chances of getting the black one. And this is exactly what happens with rough numbers. There is still a significant chance (7%) that if you ask me what colour the sheep are, I will answer black. That might look like a silly example, but this is not really far from what the reality of our data work is. There is no obvious answer and most of the time we spend is used to make sure we understand what the data we have actually means, and what should be included or not in the analysis/result.

You have to understand what actually happens when a data scientist looks for a number. They spend 95% of their time trying to figure out what data to use, what to exclude, how to connect what in theory is completely unrelated data together. They make sure to exclude some exceptions, legacy stuff etc. They need to understand how the data is produced and how exactly it will answer what we want. Then they spend 5% of their time building the graph you asked for. So it is really hard to randomly cut in the 95%, or to fly with only intuition.

How should you think about it

I also understand, we don’t want to answer every single thing perfectly, time is key. But what you have to ask yourself as a DM when I request a data point with 90 or 80% confidence is, Am I ok making a decision if there is a 10% risk that my data insight is COMPLETELY off, like saying the total opposite.

So how does time help to make a decision

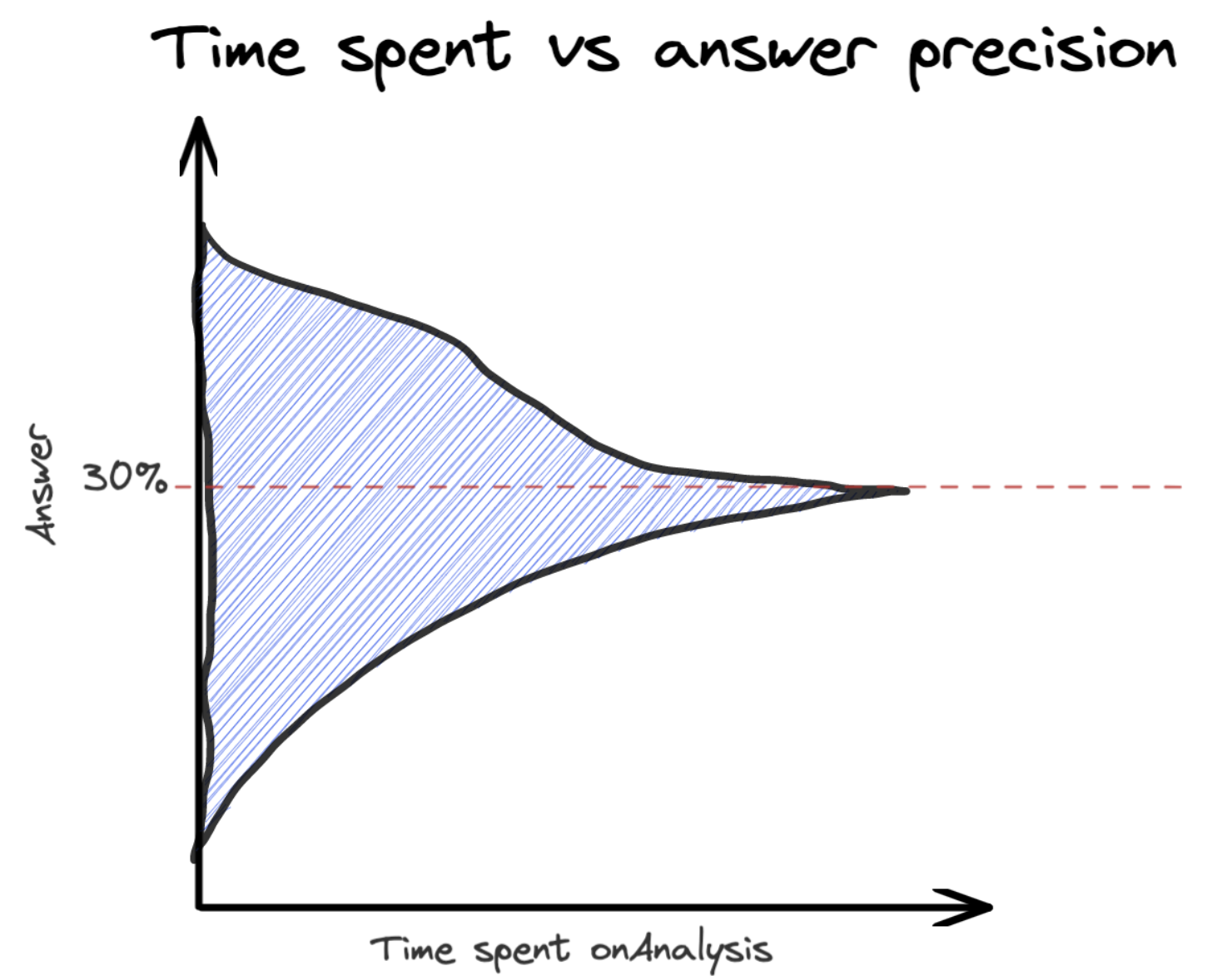

Let’s compare those 2 scenarios, 1 how I think most DMs see the relation between time and answer confidence, and how is really the relation between time and answer confidence.

How non data people see Time to Precision Ratio

My impression (and please correct me if I am wrong) is that the longer a data scientist works on a problem, the closer they get from the answer, basically the range is just getting smaller.

Something like:

- 1 Hour of work, possible answers: Between 20% and 40%

- 2 Hours of work, possible answers: Between 23% and 37%

- 3 Hours of work, possible answers: Between 25% and 35%

- 4 Hours of work, possible answers: Between 27% and 32%

- 5 Hours of work, the valid answer: 30%

So basically the answer just becomes more precise but it is always decently good.

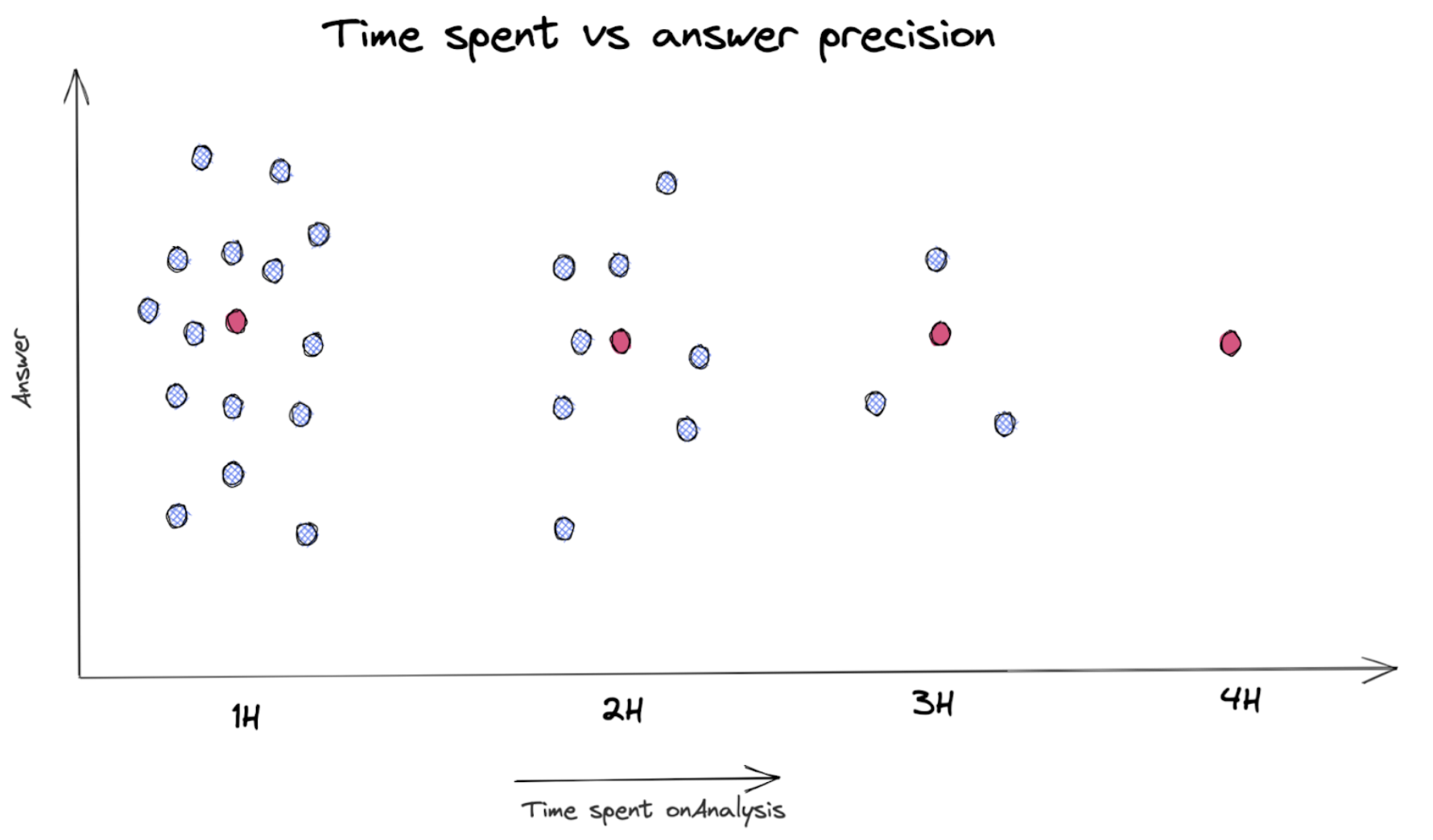

But the reality is more like this:

(where the valid answer is that the red dot and the black dot are completely wrong numbers.) So the time to ratio looks more like:

- 1 Hour of work, 1/22 to get the right answer (30%), and 21/22 to get any answers (between -100% and 100%)

- 2 Hours of work, 1/11 to get the right answer (30%), and 10/11 to get any answers (between -100% and 100%)

- 3 Hours of work, 1/3 to get the right answer (30%), and 2/3 to get any answers (between -100% and 100%)

- 4 Hours of work, 100% chances to get the right answer (30%)

Of course, we never reach 100% of confidence, but this is only to visualize what the reality of data investigation is like.

Some nuance

Over the years, I have worked with a really, really good DM, and I learned to work with a lower level of confidence based on the impact of the decision we want to make with it. In other words, for some decision we can afford to be wrong, it is even better to be wrong 1 times out of 20 but to do everything 2 times faster, than being correct all the time but to take more time, as long as you know that 1 of those 20 decisions will be wrong and you are comfortable with it.

Of course, this is where you see the best data scientist. They have the ability to invest the right amount of time to make sure they don’t give complete outliers and that their answer fit in a comfortable range.

Conclusion

What I am trying to say here is not that we should always reach 100% confidence in our usage of data to make any decision. It is rather that you have to be comfortable with the risk of being completely wrong with a specific data point if you want to use “just a quick number”. There is a reason why your favourite data scientist might be nervous when you ask for a quick number.